“Goddess is a metaphor for the great force of creativity

and compassion that underlies existence”.

Starhawk

Before you go running off to New York, remember this exhibit was in 2010...sorry about that. I just thought it was worth commemorating here, as written.

Observations on The Lost World of Old Europe Exhibition

by Lydia Ruyle, Artist, Author, Scholar

One of the highlights of a holiday trip to New York City in 2009 was a

visit to The Lost World of Old Europe, The Danube Valley, 5000-3500 BCE

exhibition at New York University. We arrived just after a huge

snowstorm had blanketed the east coast. The city streets were piled with

snow and ice and we were bundled up from head to toe to deal with the

cold.

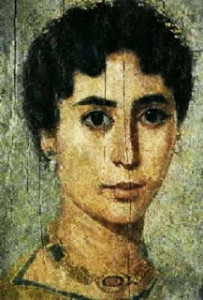

A large banner with a Goddess image on it stood at the entrance to

the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World building a block east

of the Metropolitan Museum of Art on 84th. Walking inside, we deposited

our gear in a closet and walked into the surprisingly small exhibition

space. Visually the entire exhibition is a celebration of the feminine.

A case with a vessel, a large map of Old Europe, and an introduction

to the exhibition are on the wall in the foyer. The introduction

states:

“In 4500 BCE, before the invention of writing and before the first

cities of Mesopotamia and Egypt were established, Old Europe was among

the most sophisticated and technologically advanced regions in the

world. The phrase “Old Europe” refers to a cycle of related cultures

that thrived in southeastern Europe during the fifth and fourth

millennia BC. The heart of Old Europe was centered in the Danube River’s

fertile valleys, where agriculturally rich plains were exploited by

Neolithic farmers who founded long lasting settlements—some of which

grew to substantial size, with populations reaching upward of 10,000

people. Today, the intriguing and enigmatic remains of these highly

developed cultures can be found at sites that extend from modern day

Serbia to Ukraine. The Lost World of Old Europe: The Danube Valley,

5000-3000 BC presents extraordinary finds from the three countries with

the richest Old European archaeological heritage—Bulgaria, the Republic

of Moldova, and Romania.

While Old Europe can be defined geographically with relative

simplicity, the identification of cultural groups who lived there is

more complicated. Since these cultures did not leave behind any written

sources, the material remains from excavated settlements are the only

tools that scholars can use to reveal both localized and common customs.

Archaeological exploitation began throughout the region at the end of

the nineteenth century but systematic excavations did not commence until

the 1930s. During these formative years, when a common Old European

culture had not yet been identified, archaeologists began classifying

individual cultural groups based upon the site where each was first

recognized. Hence, the Cucuteni culture is named after the modern

Romanian village of Cucuteni, where the first remains from this culture

were excavated. The same is true for the lower Danube site of Gumelnita

and Hamangia, and Varna in Bulgaria, all highlighted in this exhibition.

Modern observers have projected quite different visions on the

remains of Old Europe. But this much is clear—far earlier than is

generally recognized, southeastern Europe achieved a level of

technological skill, artistic creativity, and social sophistication that

defies our standard categories and is just beginning to be understood

in a systematic way. New studies of old collections, future excavation

projects, and exhibitions such as this one hold out hope for a clearer

understanding of Old Europe, the first proto civilization of Europe

itself.”

There are two rooms for the exhibition which you can see from the

foyer through tall glass doors. One is filled with exquisite ceramics,

large and small, small gold objects and items made from spondylous

shells which were traded across the Danube area. A raised rectangle

platform displays the ceramics at waist level making it very easy to see

the details. The size of some of the vessels is astonishing, some two

to three feet in diameter. The patterns and details on the full rounded

vessels are stunning. The artistic ability and skill to create the

vessels, decorate them with symbols and the technology to fire them in

kilns are most impressive.

A figure seated in a vessel decorated with symbols connects a female

figure with vessel as a shrine. There are also several large clay

figures of females, approximately twelve to fifteen inches high which

are hollow, in cases along the wall.

I’ve found only by actually seeing and experiencing objects can you

appreciate their scale and detail. I use what I call my artistic sight,

trained now for over fifty years, to see, feel and touch the gorgeous,

sophisticated objects. The ceramics symbolize to me the abundance of

creation and creativity in female forms.

The second room, which you enter by parting two tall glass doors,

felt like entering a shrine or sacred space. At the center of the room

across from the doors is a case with the Thinking Man and Thinking Woman

in it. The Thinking Man has breasts and I think is a female. Douglas

Anthony, one of the exhibition curators, stated in a radio interview

that The Thinking Man could be a woman. Hooray Women can think

Amazing

In the middle of the room are two cylinders lighted from within

displaying groups of clay figurines, one titled a Council of Goddesses.

One cylinder has the figures arranged in a circle, the other has the

figures in a vessel. The figures are small, the largest perhaps eight

inches, and half of them are seated on seats or thrones.

The text labels on the circle of figures states:

“This group of twenty-one figurines (thirteen large and eight small)

was found together with fragments from two large ceramic vessels, one

meant to contain them and the other functioning as a lid. The figurines

and the fragments were placed adjacent to a hearth inside a large

building, interpreted as a sanctuary, which from archaeological remains

appears to have been intentionally destroyed by fire.

Originally wrapped in straw to protect them, the figurines can be

identified as female by their clearly marked anatomy. All have

schematically rendered bodies with abbreviated heads and arms, and

exaggerated hips. The thirteen larger statuettes are set apart from the

eight smaller ones by their painted decoration and the individualized

chairs that accompany them. Two of the figurines could possibly be

identified as senior by the fact that they sit on horn-backed thrones, a

type of seating that in later cultures held ritual or religious

significance. The intentional placements of these figurines next to a

hearth, the emphasis on female anatomical details, and the hierarchy

among the statuettes have prompted some scholars to identify the group

as a “Council of Goddesses.” The lack of specific information concerning

a Cucuteni or Old European pantheon, however, prevents a specific

identification of this intriguing collection.”

The second lighted cylinder features figures seated around a central

opening in a shrine like vessel again connecting figures with vessel

suggesting female ritual in a defined ritual space.

There are cases around the room with more figures in them. An explanation text on the wall in the second room states:

“Old European Figurines: Materials, Composition and Technique

Anthropomorphic figurines were fashioned by Neolithic cultures from

Anatolia to Thessaly, from Egypt to the Levant, and from Mesopotamia to

Southeast Asia. Made in a wide array of materials—stone, metal, fired

clay, ivory, shell, and bone—they are found in domestic and funerary

contexts and probably played a central role in the social and ritual

life of the communities producing them.

Among Old European cultural groups, figurines were predominantly

modeled in clay. Bodies were usually composed of two modeled pieces that

were pressed together and then covered with an additional layer of

clay. For larger figurines, a two-piece mold may have been used. The

body of each figurine was then decorated. Pierced holes, incision work,

and painted motifs were frequently used to enliven the surface. After

firing, small attachments, often in copper, were inserted in the holes

as ornaments.

Each cultural group living in the Danube Valley developed a unique

tradition for the depiction of the human body, favoring specific shapes,

forms, and decoration. For example, the Cucuteni culture created highly

stylized bodies with abbreviated heads and arms, and decorated them

with extraordinarily precise incision work and painted motifs to create

complex series of signs and symbols. In contrast, the Hamangia culture

preferred more accurate representations or figures that combined

realistic bodies and unrealistic “pillar” heads, while generally

avoiding painted decoration.

An element common to all figures is their miniaturization. The small

size, resulting from compression and abstraction of the human body,

must have been fundamental in defining the function and meaning of these

objects. It has been suggested that they were used in initiation rites,

to prompt narratives or as magical depictions of deities. Regardless of

the various interpretations, it is certain that the size allowed a

person to interact with these tiny bodies, moving and arranging them

with respect to surrounding space and to one another, thus creating a

highly individualized relationship between each user and the figurines.

The female figure was of great symbolic significance during the

Neolithic period, as attested by a proliferation of figurines in a

variety of materials, here including stone, lime plaster, and clay.

Although we cannot be certain whether these figures represent humans or

deities, some scholars have identified them as representations of a

Mother Goddess, possibly linked to the importance of fertile land in

agricultural societies.”

(underlined emphasis mine)

The majority of the figures are small and female in form. Usage of

the term figurines rather than figures suggests to me a subtle method of

diminishing their significance as sacred objects. Their size could be a

function of the physical properties of clay itself as larger figures

must be hollow in order to keep clay from exploding at high firing

temperatures.

The texts for the objects and explanations attempt to reflect a

“scientific” left brained approach to the material. I included the

mounted texts from the exhibition in this review in order to give a

framework for what the exhibition organizers present. Like any selection

process, the objects chosen and the texts are the choices of the

organizers. I do not interpret them as negative just limited as to the

concept of a Goddess. For me, the missing element is the artistic

spiritual insight of the material which celebrates the fecundity and

abundance of life in the female form as a Great Goddess. I agree with

Starhawk that “Goddess is a metaphor for the great force of creativity

and compassion that underlies existence”. From my experience, western

archaeology avoids the term. Eastern European archaeology uses the term

Goddess with respect and reverence.

------------------------------

The perfect artist/scholar to review this exhibit, find out more about Lydia Ruyle.....

Getting inside her head:

"Seeking with my mind and body, knowing with my inner being, life

gives me wake-up calls. Art and the Ancient Mothers call me on a

journey. Art is my soul language. I create because I must. After

exploring many media, I began to make icons, sacred images of the divine

feminine, to tell herstory and share my art with the world."

--- Lydia Ruyle

To see Lydia's incredible banners, true

Ambassadors of Goddess, that have traveled around the globe for years raising awareness of the Feminine, go to www.lydiaruyle.com

The Goddess figure featured on a banner outside the exhibition and on

the front page story in The New York Times about the exhibition opening

is similar to Cucetani Venus, a Goddess Icon Banner Lydia created in

2006 for an Archaeomythology Conference at the Brukenthal Museum in Sibiui, Romania.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

Source:

http://www.examiner.com/article/goddess-of-old-europe-debuts-new-york-exhibit-at-new-york-university

Please note, by checking for info on Lydia Ruyle, I only was able to get a link that worked to her art, which is very interesting!

http://www.lydiaruyle.com/artpage1.html

Crucifixion Triptych I, 1977

Crucifixion Triptych I, 1977